How to Stop Overthinking Social Interactions (Part 1 of 2)

Or, what to do when your brain replays that conversation 400 times

Hi everybody!

Longtime dear reader Rocky writes with a straightforward question:

How do you recommend conquering post-event processing?

Rocky hits on one of the most common—and painful—features of social anxiety. Post-event processing is the technical term for overthinking, obsessing, dwelling, ruminating, and kicking ourselves with our social lowlights.

In psychologese, post-event processing is our [insert academic voice here] “repetitive consideration and potential reconstruction of our performance following a social situation.”

In practice, it’s logging off your Zoom interview and replaying all the questions you wish you had answered differently. It’s analyzing and re-analyzing the awkward silence on your date. It’s coming home from a night out and asking ChatGPT if your friends think you’re annoying.

Why do we do it? We’re trying to buy ourselves social safety. We’re trying to reduce uncertainty and reassure ourselves that we’re safe by reviewing our interactions and asking, “Am I ok?” “Did I do things right?” “Am I in danger of being criticized, judged, or otherwise socially rejected?”

But, like all safety behaviors—the behaviors we do to avoid and reduce our anxiety—post-event processing backfires because it focuses all our attention on our perceived mistakes, makes us feel like we’re in greater social danger than we really are, and, ironically, increases our anxiety about future social interactions.

Therefore, over two newsletters, we’ll go over lots of methods to quell post-event processing. Let’s start with four today (well, three things to try and one thing to stop) and we’ll cover a bunch more in the next installment. Here we go!

1: Take your thoughts less seriously.

Imagine you’re walking down the street and you spot a frenemy walking in your direction. You like the “friend” part of them—they’re familiar, you know them well, you know deep down they’re protective of you. But you also find the “enemy” part extremely annoying—they always know how to put you down and make you feel insecure. They’re getting closer, you can’t avoid them, and you know a conversation is imminent.

You have two choices in this conversation. On the one hand, you can listen closely to what they say and take their comments very seriously. You can take their backhanded compliments to heart. You can compare yourself to their humblebrags. You can receive everything that comes out of their mouth as honest truth.

On the other hand, you can listen politely but not take anything they say particularly seriously. You can watch and listen with some non-attached perspective. Of course they’re paying you backhanded compliments and humblebragging—they’ve done that for years and this conversation won’t be any different. You nod and smile, but just let the words pass you by—after all, this is your frenemy, so of course this is happening. This is what they do.

Okay, now apply this to your brain and post-event processing. What are your hot spots? After a date? After hanging out with your intense, impassioned extended family? After a work event?

Think of your post-event processing as the frenemy. The thoughts will come—you can’t turn them off or you would have done that long ago. Just like you can’t avoid the run-in with your frenemy, you can’t avoid the thoughts that come after a social interaction.

But you can take the thoughts less seriously. These thoughts are just what happens after a meeting with your boss/Hinge date/college friends hangout. You’ve been through this often enough that you don’t have to take what it says literally. Just watch the thoughts play out with the same detached politeness you’d extend to your frenemy, then go on about your day.

One-line summary: Rather than trying to change your post-event processing thoughts, change your approach to your post-event processing thoughts.

2: Turn questions into statements and then challenge them.

“Did that come off wrong?”

“Does she think I’m stupid?”

“Did I offend him?”

When our thoughts are circling the drain of post-event processing, we often phrase them as questions: “Did they think I was judging them?”

But we can’t argue with a question. If you find yourself posing your thoughts as questions, change them into statements. For example, “Should I have said good-bye differently?” turns into “I should have said good-bye differently.”

There. Now that it’s a statement, you can do more with it:

You can push back on your thoughts: “There are lots of ways to say goodbye. Besides, I was polite and sincere and that’s what matters, even if I was awkward about it.”

You can use self-compassion: “I’m being really hard on myself. Good-bye was less than 1% of our conversation. I can cut myself some slack.”

You can use acceptance: “Well, it’s normal to wish I had done some things differently. Literally everybody has little social regrets sometimes.”

One-line summary: Turn questions into statements to get more traction for whatever coping you use next.

3. Differentiate possibility from probability.

We’re designed to jump to the worst-case scenario. After all, our brains are trying to keep us safe and it’s better to mistake a harmless sheep for a dangerous wolf than miss a wolf, thinking it’s a sheep.

But that means we overestimate the chances of bad things happening. We mistake possibility for probability. Was your colleague offended that you changed the subject during your conversation? Possibly—anything is possible. But probably not. Does your friend secretly hate you because you were 10 minutes late, even though she said she totally understands that life happens? Possibly—she might be secretly harboring a grudge. But probably not.

Whatever your worry, it is indeed possible that your feared outcome will come to pass. However, you’re a reasonable person. If the tables were turned, would you have the reaction you’re worried about? Maybe. But I’ll bet you a cockatoo probably not.

One-line summary: Just because a feared outcome is possible, doesn’t mean it is likely to happen.

4: Counterintuitively, don’t journal about it.

In cows, rumination is the process of regurgitating and re-chewing partially digested food. Appropriately, our own mental rumination includes going over and over partially digested negative interactions. Therefore, resist journaling if you’re essentially ruminating on paper.

Journaling is supposed to be “good for us,” but just like anything, it depends on your situation. If journaling makes you feel better—maybe you do digest those worries!—please keep doing it. But if you end up spinning your wheels or making your worries grow full and lush, close the journal and back away slowly.

One-line summary: Resist journaling if it’s functioning as worrying on paper.

Tune in next time for more tools in Part 2! Until then, be good to yourself—I guarantee you’re doing better than you think.

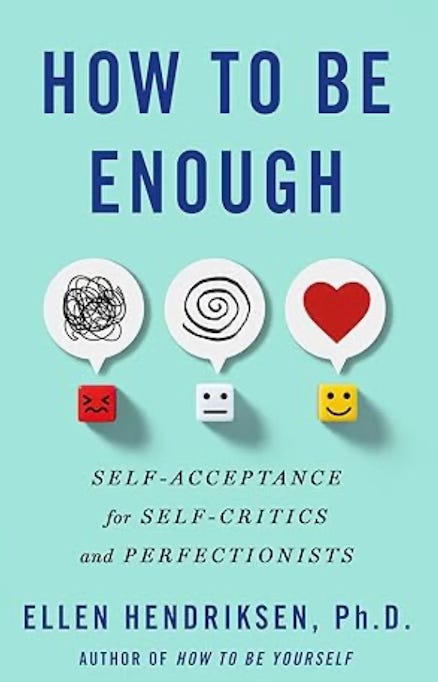

We’re closing in on 100 reviews! Leaving a short, honest Amazon review makes my book feel seen! It’s been working hard since January, so thanks for making its day!

Be kind to others and yourself!

I had to re-read this today….Completely interrupted a co-worker today during a Zoom call while she was presenting. Apologized and she said it was fine but couldn’t stop kicking myself.

Thanks! New to Substack and excited to be here!